Office of the Police Commissioners

For the City of St. Louis.

April 12, 1861.

It being of absolute necessity for the peace and quiet of the city that the law in respect to the Sabbath, commonly called the Sunday law, shall be strictly observed, it is hereby ordered that all shows, games, exhibitions, plays, and fights of man and beast, sales of liquor, or other violation of said laws are forbidden, and notice given that the penalties against the violation of said laws will be strictly enforced.

J.A. Brownlee, President.

-History of Saint Louis City and County: From the Earliest Periods to the Present Day: Including Biographical Sketches of Representative Men, Volume 1

|

The above comes from an 1883 book by John Thomas Scharf and I read the reference to "games" as very likely referring to baseball. The history of Sunday baseball in St. Louis is an interesting one and I don't think I've ever done the subject justice. One of the points I always like to make, with regards to Sunday baseball in St. Louis, is that the French, Creole, Catholic cultural influence on the city had a important impact on how the Sabbath was celebrated and on how the locals viewed Sabbatarian laws. There were attempts, periodically, to enforce these blue laws with regards to baseball during the 19th century but they always failed. Sunday baseball was a big part of the culture of St. Louis during the second half of the 19th century and these attempts to suppress that always came to nothing because they never had the support of the citizens of St. Louis. Tough to enforce a law when the citizens oppose it.

0 Comments

Anniversary of the Empire Base Ball Club Anniversary of the Empire Base Ball Club.-The Empire Base Ball Club will celebrate its second anniversary to-day, by a game and festivities at Gamble Lawn. At 2 ½ P.M. the members, with numerous invited guests-ladies and gentlemen, are expected to meet at the above named spot, where ample preparations will be found to have been made for a joyous occasion. A match at base ball will first come off, between nine of the club’s best players on one side, and nine more of them on the other. Refreshments and additional social delights will follow. We are authorized to extend a general invitation to our citizens and their ladies to be present. The Match Game of Base Ball.-The proposed game of base ball between the two select parties, nine in each, of the Empire Base Ball Club, was yesterday prevented by the storm, but will come off at 2 ½ P.M. to-day, at Gamble Lawn, in the style heretofore announced. So I was going through my notes (which are a disorganized mess), looking for information about St. Louis baseball in 1865 when I found a file I forgot I had. In this file was a bunch of stuff from the St. Louis Daily Press of 1865 and a few notes from the Missouri Democrat of 1861. About five years ago, it seems I went to the library in St. Louis and went through the microfilm archives of the Daily Press and the Democrat. I have absolutely no memory of doing this but it must have happened because there is no other way that I could have gotten this information otherwise.

We'll get to the stuff from the Daily Press when we're done with 1864 but I wanted to put up the stuff from the Democrat while I have the file open and I'm thinking about it. There are only four references to baseball in my notes from the 1861 Democrat and one of those is a notice for a meeting of the Laclede Club that also appeared in the Republican. So we'll skip that. The other three references are posted above and mention the Empire Club's first anniversary game. We'll add a link to this post to the 1861 page so I don't forget this stuff again. The news of the battle of Wilson's Creek elated the Secession elements all over the State. The report reached St. Louis on August 13th and carried grief and anxiety into many families who had members in Lyon's army...The awful meaning of war was now realized by all those who had never been through that terrible ordeal before; even the safety of the City of St. Louis was questioned, and General Fremont issued the following order: It seems that I keep coming back to August 1861. Both Lafayette Park and the Fairgrounds, two of the three most used baseball grounds in St. Louis, were occupied by Union troops at that time and I find that rather significant when we're looking for specific ways in which the Civil War depressed the growth of baseball in St. Louis.

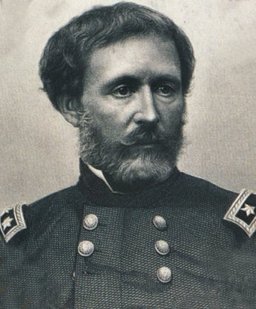

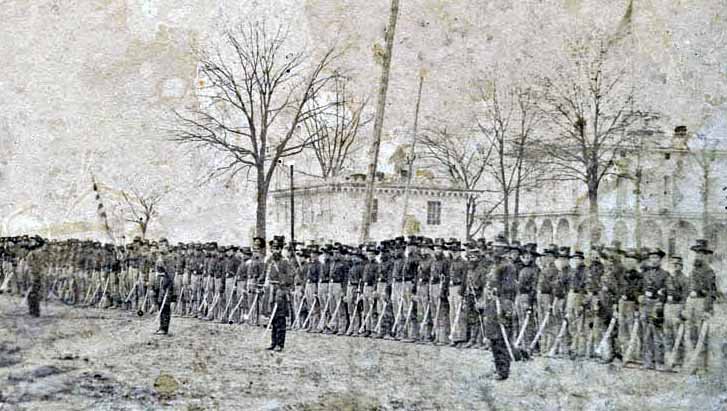

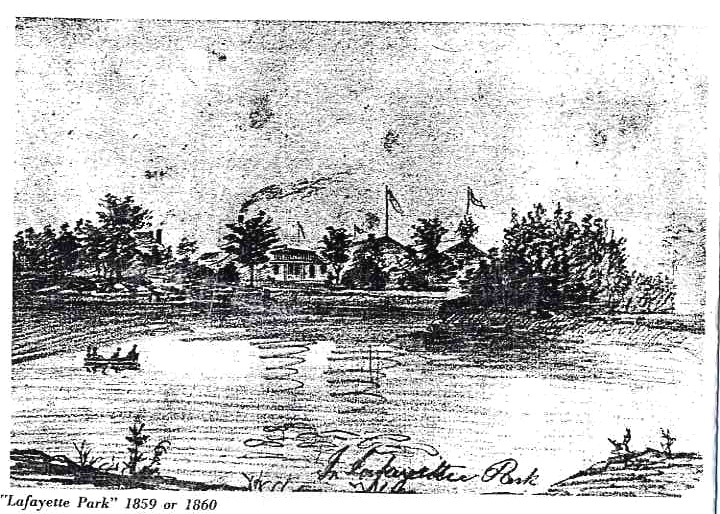

Here, in Robert Rombauer's fine book, we find John Fremont's order to occupy Lafayette Park. We get a specific date for when it happened and a reason why it happened. So I think that's worth taking a quick step back and revisiting 1861. Before we finish up 1862, I need to take a step back and talk about Benton Barracks. To save us (and by us, I mean me) a little bit of time, I'll just quote from the Trans-Mississippi Theater Photo Archive website: Located on the north side of St. Louis, Benton Barracks was one of the most important Union Army training camps in Missouri during the Civil War. The 150-acre complex was established in 1861, and contained barracks, warehouses, and numerous other buildings. A number of Missouri Union regiments were organized there, including some of the state’s African-American units. Soon after the war, the camp was closed and nothing remains of the wartime home of thousands of Federal soldiers. So that's interesting but what does it have to do with St. Louis Civil War baseball? Well, the location of Benton Barracks was significant. The collection of troops and war material in the neighborhood of St. Louis in August [1861] was of the most formidable character. At Camp Benton, immediately west of the Fair Grounds, extensive preparations were being made for the accommodation of a large body of troops, but only two regiments had taken post in this vicinity on the 21st. According to John Thomas Scharf's history, Benton Barracks was located west of the St. Louis Fairgrounds, which just so happened to have been one of the primary antebellum baseball grounds in the city and the location of the first match game ever played in St. Louis. Combine this with the fact that Union troops were also using Lafayette Park as a camp and we now know that by August of 1861, Union troops had occupied two of the three most used baseball grounds in St. Louis.

If we're looking for specific reasons why the war stunted the growth of baseball in St. Louis and across the nation, we find in this information something that I don't think has ever really been considered. Peter Morris, in But Didn't We Have Fun?, talks about how the availability of open field space in antebellum America was a significant contributing factor in the spread of baseball in the late 1850s. Here, early in the Civil War, we find that availability being curtailed. The land that would have been used to play baseball was being used as camp grounds by the Union army. In the specific case of St. Louis, we find the Union army using some of the very best and most popular pieces of land. We see the impact of this in the contemporary source material. You don't see Lafayette Park and the Fairgrounds being used as baseball grounds after the summer of 1861. We now know that they were not available for use as baseball grounds because they were being used by the Union army. By August of 1861, baseball clubs were severely limited in their choice of grounds. The only decent grounds left was Gamble Lawn. There were other grounds being used in the city, such as Carr Park, the Laclede Grounds, and the Veto Grounds, but it appears that the best clubs, that had played at Lafayette Park and the Fairgrounds in the past, were pretty much limited to Gamble Lawn if they wanted to bring in a crowd. I would argue that this limitation in choice of grounds had a depressing effect on the growth of the game in St. Louis and I would imagine that we would see the same thing across the North in 1861. I've archived all of the Civil War posts about 1861 on their own page. You can find it by clicking the link above, by following the link on the under-construction Civil War page, or by following the links in the left sidebar (hover over the Civil War Baseball header to bring up the 1861 page link).

On the home page, I'm continuing the "St. Louis Baseball and the Civil War" series and have moved on to 1862. With the Empires/Union match on December 19, 1861, it appears that the 1861 baseball season in St. Louis came to an end. It was, to say the least, rather eventful. What I want to do today is summarize the information that the Missouri Republican has given us and put it all in a bit of context before we move on to 1862.

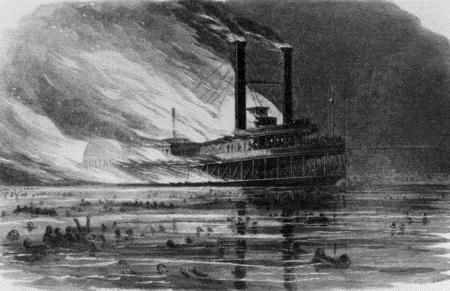

I found twenty-seven references to baseball in the Missouri Republican from 1861. This was a sharp increase from the two references I found in the Republican from 1859 and the three in the Republican from 1860. This is also substantially more references to baseball than the thirteen that I found in the St. Louis Daily Bulletin from 1860. The references in the Republican from 1861 specifically mention ten different clubs. Prior references in the Republican, in 1860, only mention five clubs. However, the Daily Bulletin, in 1860, mentions eight clubs. If we want to be technical about the number of clubs the Republican mentioned in 1861, there were actually only eight, with two of the clubs having junior nines. Then again, the Republican did report on a game played by a second nine of the Union Club. So, in 1861, we have eight clubs, two junior nines and a second nine mentioned. That's a total of eleven nines mentioned in the Republican. All of the clubs mentioned by the Daily Bulletin in 1860 were still active in 1861 and mentioned in the Republican except for the Lone Stars. The only clubs mentioned by the Republican and not by the Daily Bulletin were the Lacledes, the Commercial, Jrs., and the Excelsior, Jrs. There were fifteen games of baseball mentioned in the Republican in 1861. Seven of these were match games played between clubs while the rest were muffin games and games played between picked nines. The Republican only mentioned two games in 1860, both match games between clubs. The Daily Bulletin, in 1860, mentioned eight games and all were match games. The Republican, in 1861, mentions three places were games were played: Lafayette Park, Gamble Lawn, and the Fairgrounds. In 1860, they mentioned games played at the Fairgrounds and the Laclede Grounds at Twenty-Seventh and Biddle. The Daily Bulletin, in 1860, also mentioned three places were games were played: the Fairgrounds, the Laclede Grounds, and Gamble Lawn. That's a lot of information and I thought about making some graphs to present all of this but then I realized I don't get paid to do this. So no graphs. But what does all of this information mean? What does it tell us about the game in St. Louis at the beginning of the Civil War? I think the only thing we can state for certain is that the Missouri Republican expanded their baseball coverage in 1861, going from three references to the game in 1860 to twenty-seven the next year. Generally, during the pioneer baseball era in St. Louis, newspapers expanded their baseball coverage when the game experienced a growth in popularity and cut back that coverage when the game's popularity began to wane. The expansion of baseball coverage in the Republican in 1861 appears to be evidence of the growth in the popularity of the game in St. Louis at the beginning of the Civil War. However, in all of this information, I don't really see any evidence of the growth of the game in St. Louis. The Republican only mentions one club not mentioned in the Daily Bulletin - the Lacledes - but the Daily Bulletin, in 1860, does mention "the Laclede grounds," implying that the Lacledes were active in 1860. The junior clubs and the Unions' second nine does imply that the clubs themselves were growing and expanding, as does the reference to the honorary members of the Empire Club. But there doesn't appear that there were any more clubs in 1861 than there was in 1860. In fact, it's possible that there may have been fewer clubs in 1861, as the Republican fails to mention any activity by the Lone Stars. The Republican mentions seven match games in 1861 but the Daily Bulletin mentions eight in 1860. Does this mean that there were fewer match games in 1861 than there were in 1860? Not necessarily. One thing we have to consider is that the Daily Bulletin had better baseball coverage in 1860 than the Republican did in 1861. That's absolutely possible and could skew the superficial analysis that we're doing here. But the fact remains that we have references to more match games in 1860 than we do in 1861. One particular thing of interest here is that there is no reference to baseball played at Lafayette Park prior to 1861. Both the Republican and the Daily Bulletin mention games played at Gamble Lawn, the Laclede grounds, and the Fairgrounds. But the Daily Bulletin fails to mention any baseball activity at Lafayette Park in 1860. However, the Republican does refer to the park as the Cyclones' "old grounds," so one has to assume that the club played at the park in 1860, which is consistent with references in the secondary source material. If that's the case then there are no new grounds mentioned in the Republican in 1861. I would imagine if the game was growing and there were a substantial number of new clubs then one would see new grounds being used. But we don't see that. So where does that leave us? We have an increase in baseball coverage in the Republican and a likely increase in the size of the previously existing baseball clubs in 1861. But we don't see an increase in the number of clubs, the number of matches, and the number of grounds used. I actually find that to be particularly surprising. Prior to looking at all of this, I would have stated that we did see an increase in the number of clubs and matches between 1860 and 1861 in St. Louis. But there is no evidence to support that. This is not what I expected to find when I began comparing the data. There is an ongoing argument within the 19th century baseball research community about the impact that the Civil War had on the growth and evolution of baseball. There is no doubt that the community has been moving away from the idea that the war helped spread the game and was responsible for the post-war baseball boom and towards the idea that the war impeded the growth and spread of the game. I am, essentially, in the latter camp and will, at some point, explain my thinking with regards to that. But I have been amazed, over the last few years, by how much more information I've found about baseball activity in St. Louis during the war years then I thought I would find. The secondary sources - specifically Tobias and Spink - had lead me to believe that there was very little going on in St. Louis during the war and that has turned out to be absolutely not true. There was a great deal of baseball being played in St. Louis during the Civil War and that's really what this entire series is all about. I think the fact that I thought I'd find very little baseball activity in St. Louis during the war and ended up finding a lot has clouded my thinking about the impact of the war on baseball. I was kind of getting away from the idea that the war had a negative impact on the growth of the game and leaning towards this notion that the war had little to no impact on the game's growth in St. Louis - that the game grew and expanded in St. Louis despite the war. But, when taking a closer look at the evidence, I don't see much growth in 1861. There aren't more clubs. There aren't more match games. There aren't more grounds. I just don't see much evidence to support the idea that baseball was growing in St. Louis in 1861. I believe, based on the increase in newspaper coverage in the Republican, that the game was becoming more popular and it's entirely possible that the existing clubs were larger and playing more intramural games and muffin games than they were in 1860. So to that extent, the game was growing in St. Louis. But I had expected to see much more than that. I thought there were more clubs and more match games in 1861 than in 1860. Based on the evidence I have, I was wrong to believe that. The big question here, of course, is was this lack of growth a result of the Civil War? I believe that it was. St. Louis, in 1861, was a city at war. A battle was fought in the city in May. Men were joining up and leaving the city to go fight. Martial law was declared in August. There was most likely a Confederate terrorist cell in the city setting fire to steamboats. St. Louis was a city with divided loyalties caught up in the madness of a civil war. How could this not have an impact on someone's desire to go play baseball? How important could baseball be to someone living in St. Louis in 1861? If there is one thing I hope I'm achieving with this series, it's placing early St. Louis baseball in the context of the war itself. This game was played on the day that this battle was fought. I want you all to think about the game in that context. The Civil War wasn't something in a textbook for our pioneer baseball players. It was something that they lived through and experienced. It was something that had a profound impact on their lives. Edward Bredell lived through the siege of Vicksburg and died, far from home, fighting a guerrilla war against the Union. This was a man who was as significant to the early history of the game in St. Louis as anyone. How important was baseball to him when he was starving at Vicksburg? In that context, should we be surprised that there weren't a bunch of new baseball clubs in St. Louis in 1861 or that there weren't a lot more match games? In the end, I think it's really simple. Why didn't the game grow more in St. Louis between 1860 and 1861? The answer has to be that people were busy with other and more important things. I meant to post this earlier but it slipped my mind until a few days ago when I was looking something up in Louis Gerteis' fine history of St. Louis during the Civil War. Better late than never. By summer 1861, St. Louis had become the staging ground for federal military operations in the lower Mississippi Valley...The husband of Sarah Hill, a builder by trade, had joined the federal army and served throughout the war as an engineer. She visited him at his camp in Lafayette Park..."Beautiful Lafayette Park," recalled Hill, "with its brilliant flower beds and stretches of green sward, looking like emerald velvet, was turned into a great military camp." We have two secondary sources that mention the fact that Union troops occupied Lafayette Park in 1861, essentially putting an end to baseball activities there. The first is, of course, E.H. Tobias who, in his history of early St. Louis baseball that was published in The Sporting News, wrote that the Cyclone Club "enjoyed the benefit of the grounds for only a brief period as the war of the Rebellion had broken out, soldiers were being recruited and the military powers seized upon it as a fitting spot for an encampment." The second source is an April 21, 1895 article from the St. Louis Republic that noted that the Cyclone grounds at Lafayette Park "were occupied as a camp...with a troop of United States soldiers, and the 'Cyclones' became a thing of the past."

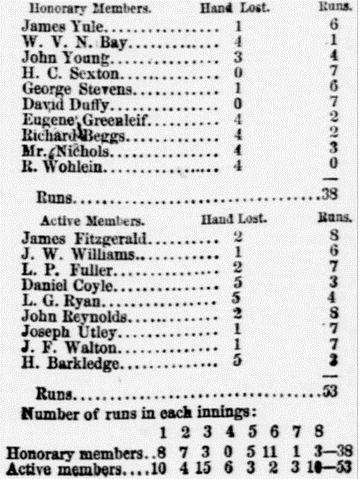

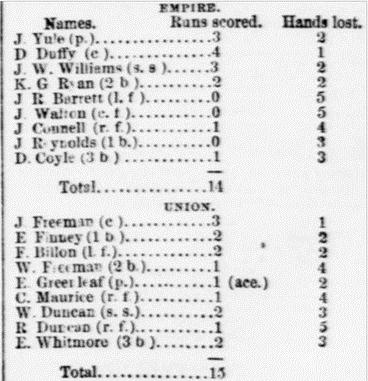

The article in the Republic, which was most likely written by Tobias, was basically a history of the Cyclones and quoted Leonard Matthews, Ferdinand Garesche, and Maurice Alexander. I've always found it interesting that Tobias essentially blames the breakup of the Cyclone Club on the occupation of their grounds by Union troops. We know that the Commercial Club was also using the grounds at Lafayette Park and the loss of those grounds didn't stop them from continuing on. The loss of the grounds may have been the final nail for the Cyclones but they had torn themselves apart in the spring of 1861. There was no way that a club with people like Basil Duke and Edward Bredell on one side and Merritt Griswold and Orville Matthews on the other was going to survive the outbreak of war. But it is interesting that Leonard Matthews, Garesche and Alexander were telling Tobias that the loss of the grounds ended the club. I don't really think it's true but it is interesting. I've never found a lot of information about what was happening in the park after it was occupied and have never been able to find out when exactly the troops took over the park. The last game that I know was played at the park in 1861 took place in early June. Based on the journal of Sarah Jane Hill, we know that the troops had encamped at the park by August 2. So sometime in June or July of 1861, Union troops took over Lafayette Park and baseball activity there ceased. To the best of my knowledge, baseball games were not played again at the park until 1863. Base Ball - A match came off yesterday afternoon between the Active and the Honorary members of the Empire Base Ball Club, with the following result: We learn that our lymphatic friend Henry Clay Sexton, Counsellor W.V.N. Bay, Justice Wohlein, Deputy Sheriff George Stevens and others of the honorary department, "shed" their clothing only to come out of the contest losers - the "runs" being against them, 53 to 38. Steamboat Burnt. - The steamboat E.M. Ryland was destroyed by fire shortly after 5 o'clock, yesterday afternoon. The boat had been lying a short distance below Lesperance street for some time past, and it is probable was fired by incendiary. The flames, after getting under headway, spread with great rapidity and rendered useless all attempts to extinguish them. The boat was burned to the water's edge. Another boat, lying near by, was at one time in great danger of being destroyed. My favorite baseball quote comes from the above mentioned Henry Clay Sexton. "The game of baseball," Sexton once said, "is now wonderfully perfect and I never tire of looking at it..." That's just fantastic and I think it sums up how a lot of us feel about the game.

Sexton is one of the more interesting figures of St. Louis baseball history. He was the longtime president of the Empire Club and was also the first chief of the St. Louis Fire Department. Sexton was also arrested during the war and charged with having pro-Confederate sympathies, spending some time in Gratiot Street Prison. I always found it interesting that after the war, Sexton regained both the presidency of the Empire Club and his post as Chief of the StLFD. I think that says something about both the Empires and the city. The man was also a decent ballplayer, as the above box score will attest. The other squib that I posted from the Republican is of some historical importance. The burning of the E.M. Ryland was the first boat-burning in St. Louis that the Union authorities attributed to sabotage. The boat-burnings are a little-known, but fascinating, part of the war in the West and Civil War St. Louis has a ton of information about it. I would particularly recommend G.E. Rule's piece on Jospeh Tucker. Essentially, what you had here was an underground Confederate force that was destroying steamboats in an attempt to disrupt Union supply lines in the Western theater. I'm not sure how organized the effort was in 1861 but by 1863 the boat-burners had received official Confederate sanction and in the fall of that year, there were two separate attacks that destroyed seven steamboats. The burning of the E.M. Ryland was most likely the first attack by the boat-burners in St. Louis and it took place on the same day as the match between the playing and non-playing members of the Empire Club. Base Ball Match - The following is the result of a match game of base ball played yesterday, on Gamble's Addition, by the Empire and Union Base Ball Clubs of this city: [Unions 15, Empires 14.] At the old blog, I wrote the following about this game: I think this is most likely the first game ever played between the Empire and Union clubs. Tobias wrote that the Unions had organized in 1859 and that this game took place during the "holidays of '60..." He had the score right but was off by a year. He also mentions a series of games between the two clubs that took place in "1860 and the early part of '61..." Again, he was off by a year, as I also now have primary source evidence of the first Empire/Union series taking place in 1862. Three days after the first Empires/Union match, the first Confederate prisoners arrived at the Gratiot Street Prison. The Prisoners - Preparations for their Accommodations. - A portion of the large number of prisoners, recently captured by Gen. Pope, were expected to arrive at the Pacific Depot last evening, but up to a late hour the train upon which they were expected had not made its appearance. They are to be quartered at McDowell's College, or as many of the whole number as that institution is capable of accommodating. About fifty workmen were yesterday engaged in preparing the College for their reception. Among those thus engaged were fifteen or twenty contrabands, who are at present in charge of Jailor Roderman. They were taken out of jail for the purpose named. In cleansing the College and clearing out the rubbish in the basement, two or three wagon loads of human bones were found. Skulls, arms, legs, ribs, and so on; the relics of various "subjects" experimented upon by the medical students in former days. The work of hauling these "relics" was very distasteful to the contrabands, and they frequently expressed their unqualified disgust thereat. As usual, Civil War St. Louis has the best information about the Gratiot Street Prison and I recommend you head over there to learn more. Here's how they describe the place: During the Civil War Gratiot Street Military Prison was operated in St. Louis, Missouri by the Union army. Gratiot was unique in that it was used not only to hold Confederate prisoners of war, but spies, guerillas, civilians suspected of disloyalty, and even Federal soldiers accused of crimes or misbehavior. The prison also was centered in a city of divided loyalties. Escapees could find refuge in homes not even half a block away. Many of the most dangerous people operating in the Trans-Mississippi passed through its doors. Some escaped in dramatically risky ways; others didn't and lost their lives at the end of a Union rope, or before a firing squad. As I mentioned yesterday, Henry Clay Sexton would spend some time locked up there as would Edward Bredell's father. I can't imagine that it was a pleasant experience.

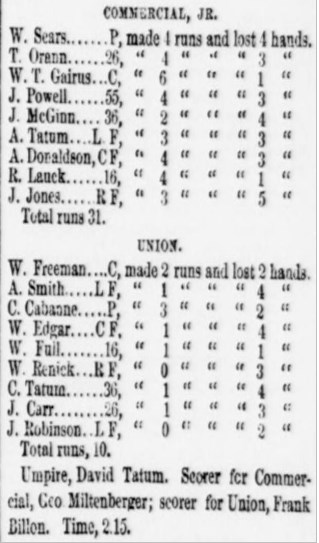

A match of base ball was played on Gamble Lawn, Saturday morning, between the Commercial, Jr., and the second nine of the Union Club, and was handsomely won by the Commercial... I love this box score.

First thing you should note is the fact that Tom Oran was playing with the Commercial, Jr., in 1861. Oran is widely - and rightly - recognized as the first Native American major league baseball player and gained that distinction by playing in the NA with the Reds in 1875. He was probably only about fourteen or fifteen years old in 1861 and just beginning what would be a rather interesting baseball career. This is the first record we have of Oran playing baseball and, therefore, is of some historical significance. The other thing you should note is the guys playing for what is described as the Union Club's second nine. Asa Smith, Charles Cabanne, Willy Freeman, Joseph Carr, with Frank Billon keeping score. All of these guys would go on to make names for themselves as ballplayers in the post-war, amateur era. The Union had themselves a pretty nice second nine that would develop a lot of the talent that would go on to win the championship in 1867. |

Welcome to This Game Of Games, a website dedicated to telling the story of 19th century, St. Louis baseball.

Search TGOG

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed