Invited To The Field: A Source-Based Analysis of Baseball in St. Louis During the Civil War

by Jeffrey Kittel

It was in the latter years of the ‘50’s that base ball found a permanent lodgement [in St. Louis] and in 1860, 1861, and 1862 it became quite “the craze,” and assumed definite proportions.

-E.H. Tobias, writing in The Sporting News, October 26, 1895

From the date of the first convention in New York [in 1857] the game grew rapidly in popularity. But the great Civil War which broke out in 1860 put a serious check to the sport, though through all the excitement of the four years which followed, a few clubs kept playing, and perpetuated the game.

-Al Spink, The National Game

There are...commonly accepted beliefs about the effect of the Civil War on baseball's history...which are incorrect, or at least only partly true. One is that baseball's growth was halted by the Civil War.

-Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills,Baseball: The Early Years

The Commercial Base Ball Club have their regular field exercise on Gamble Lawn this Saturday afternoon. Members are requested to be prompt in attendance, and Base Ball players generally are invited to the field.

-Missouri Republican, June 18, 1864

I. Saeculum Obscurum

Baseball historians do not have a good understanding of what happened to the game during the Civil War. There have been very few scholarly works devoted to the subject and there is little consensus among historians about the effect that the war had on the growth and evolution of the game. In many ways, the Civil War era is baseball's Dark Ages. There is a much better understanding of how the game grew and developed during the antebellum and post-war eras than there is during the war years. When Civil War era baseball is not being ignored by historians, due to the complexity of the subject matter, it is the subject of century-old myths that distort and confuse our understanding of one of the most interesting periods in the history of baseball.

There are, essentially, two schools of thought about the effect that the Civil War had on baseball. The first argues that the war was responsible for the spread of the game and for the post-war baseball boom. The second argues that the war impeded the growth and spread of the game. There is no doubt that the 19th century baseball research community has moved away from the first and generally supports the second. The most recent research shows a sharp, national decline in baseball activity during the war years, with few new clubs being formed and few match games being played. At the same time, there has been no research that has shown a connection between war era baseball activity and the post-war baseball boom.

But even with the work done by people like George Kirsch and the researchers at Protoball, it is still difficult to discuss baseball during the Civil War in anything but generalities. We simply do not have the evidence that we need to discuss the subject intelligently and to do anything more than speculate as to the nature of the effect of the war on baseball. What we need are facts. What we need is data. If we want to argue that the war impeded the growth of the game, we have to be able to show that. If we want to argue that the war spread the game, we need to be able to prove it. Generalities and speculation is not historical inquiry. History should not deal in myth or legend but in provable fact.

In a series of posts entitled St. Louis Baseball and the Civil War, I presented all of the material related to Civil War era baseball in St. Louis found in the Missouri Republican. At the Civil War page, you can find all of those posts, broken down by year. I had several goals in mind for this series, including wanting to put St. Louis Civil War baseball in the context of the war itself. But the main goal was to present all of the data that I had in an organized manner. I've spent several years gathering the material from the Republican, as well as information about St. Louis Civil War baseball from countless other sources, and I felt that the material that I had put together was unique. I knew that with this material I had sufficient data to test the conventional wisdom with regards to Civil War era baseball. After several years of research, I had provable facts. With this information, I believe, we can begin to move beyond generalities and speculation and speak intelligently about Civil War era baseball based upon an analysis of the St. Louis data.

What I propose to do here is to briefly summarize the data regarding St. Louis Civil War baseball. If you're interested in looking at all of the source material, you can find links to everything at the Civil War page and I absolutely encourage you to take a look at it, if you haven't already. After presenting the data summary, I'll present some conclusions based upon my understanding of the data.

I do not pretend to have all of the data and all of the source material and I do not pretend that my conclusions are facts. But we have to start somewhere.

II. The Data

All references from the Missouri Republican, except where noted.

All data for 1864/65 includes references from 1/1/64 to 5/1/65.

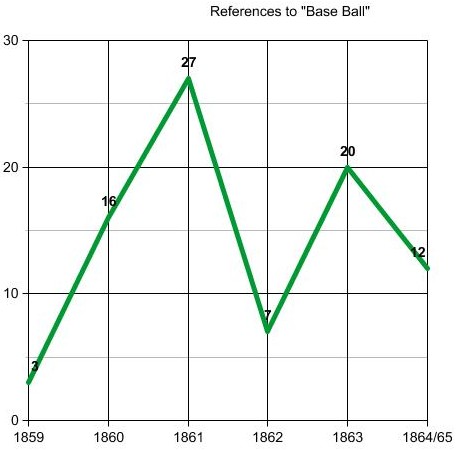

References to “Base Ball”

1859: 3 (one from NY Clipper)

1860: 16 (13 from StL Daily Bulletin)

1861: 27

1862: 7

1863: 20

1864/65: 12 (one from StL Daily Bulletin)

Total references to baseball from 1859 to May 1, 1865: 85

Baseball historians do not have a good understanding of what happened to the game during the Civil War. There have been very few scholarly works devoted to the subject and there is little consensus among historians about the effect that the war had on the growth and evolution of the game. In many ways, the Civil War era is baseball's Dark Ages. There is a much better understanding of how the game grew and developed during the antebellum and post-war eras than there is during the war years. When Civil War era baseball is not being ignored by historians, due to the complexity of the subject matter, it is the subject of century-old myths that distort and confuse our understanding of one of the most interesting periods in the history of baseball.

There are, essentially, two schools of thought about the effect that the Civil War had on baseball. The first argues that the war was responsible for the spread of the game and for the post-war baseball boom. The second argues that the war impeded the growth and spread of the game. There is no doubt that the 19th century baseball research community has moved away from the first and generally supports the second. The most recent research shows a sharp, national decline in baseball activity during the war years, with few new clubs being formed and few match games being played. At the same time, there has been no research that has shown a connection between war era baseball activity and the post-war baseball boom.

But even with the work done by people like George Kirsch and the researchers at Protoball, it is still difficult to discuss baseball during the Civil War in anything but generalities. We simply do not have the evidence that we need to discuss the subject intelligently and to do anything more than speculate as to the nature of the effect of the war on baseball. What we need are facts. What we need is data. If we want to argue that the war impeded the growth of the game, we have to be able to show that. If we want to argue that the war spread the game, we need to be able to prove it. Generalities and speculation is not historical inquiry. History should not deal in myth or legend but in provable fact.

In a series of posts entitled St. Louis Baseball and the Civil War, I presented all of the material related to Civil War era baseball in St. Louis found in the Missouri Republican. At the Civil War page, you can find all of those posts, broken down by year. I had several goals in mind for this series, including wanting to put St. Louis Civil War baseball in the context of the war itself. But the main goal was to present all of the data that I had in an organized manner. I've spent several years gathering the material from the Republican, as well as information about St. Louis Civil War baseball from countless other sources, and I felt that the material that I had put together was unique. I knew that with this material I had sufficient data to test the conventional wisdom with regards to Civil War era baseball. After several years of research, I had provable facts. With this information, I believe, we can begin to move beyond generalities and speculation and speak intelligently about Civil War era baseball based upon an analysis of the St. Louis data.

What I propose to do here is to briefly summarize the data regarding St. Louis Civil War baseball. If you're interested in looking at all of the source material, you can find links to everything at the Civil War page and I absolutely encourage you to take a look at it, if you haven't already. After presenting the data summary, I'll present some conclusions based upon my understanding of the data.

I do not pretend to have all of the data and all of the source material and I do not pretend that my conclusions are facts. But we have to start somewhere.

II. The Data

All references from the Missouri Republican, except where noted.

All data for 1864/65 includes references from 1/1/64 to 5/1/65.

References to “Base Ball”

1859: 3 (one from NY Clipper)

1860: 16 (13 from StL Daily Bulletin)

1861: 27

1862: 7

1863: 20

1864/65: 12 (one from StL Daily Bulletin)

Total references to baseball from 1859 to May 1, 1865: 85

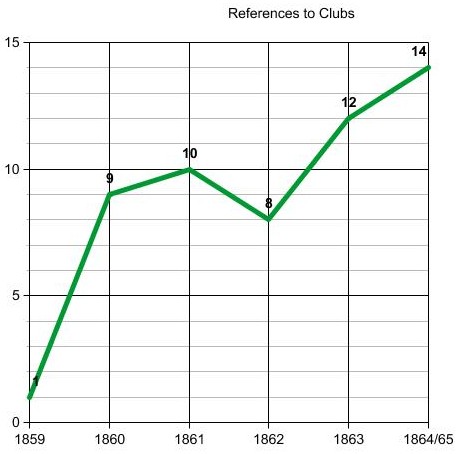

References to Clubs

Does not include any references to picked nines or second nines

* Notes a new club for the given year

1859 (1)

Unknown Club (NY Clipper)*

1860 (9)

Empire*

Cyclones*

Morning Stars*

Commercials*

Excelsiors (Daily Bulletin)*

Lone Stars (DB)*

Tigers (DB)*

Unions (DB)*

Lacledes (DB; based on a reference to “the Laclede grounds”)*

1861 (10)

Cyclones

Commercials

Morning Stars

Empires

Laclede

Commercial Juniors*

Unions

Excelsiors

Excelsior Juniors*

Tigers*

1862 (8)

Commercials

Unions

Empires

Empire, Jrs.*

Imperials*

Commercial, Jrs.

Young Union, Jrs.*

Morning Star, Jrs.*

1863 (12)

Empires

Commercials

Baltic*

Young Commercials*

Commercial, Jrs.

Union, Jrs.*

Cyclones*

Independent*

Empire, Jrs.

Hope*

Eclipse*

Lacledes (based on a reference to the Laclede Grounds)

1864/65 (14)

Enterprise*

Carondelet*

Young Commercials

Empires

Imperials

St. Louis*

Laclede

Missouri*

Hickory*

Commercials

Hope

Resolute*

Imperial, Jrs.*

Mississippi*

All Known Clubs from 1859-1864/65 (31)

Baltic

Carondelet

Commercials

Commercial, Jrs.

Cyclones

Cyclone (2)

Eclipse

Empires

Empire, Jrs.

Enterprise

Excelsiors

Excelsior, Jrs.

Hickory

Hope

Imperials

Imprerial, Jrs.

Independent

Lacledes

Lone Stars

Mississippi

Missouri

Morning Stars

Morning Star, Jrs.

Resolute

St. Louis

Tigers

Unions

Union, Jrs.

Unknown Club

Young Commercials

Young Union, Jrs.

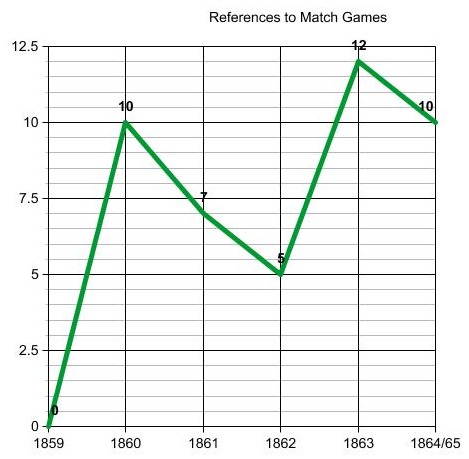

References to Match Games

1859: 0

1860: 10 (eight from StL Daily Bulletin)

1861: 7 (15 total games mentioned)

1862: 5

1863: 12

1864/65: 10 (plus one reference to “field exercises”)

References to Grounds

1859: 0

1860: 3 (Fairgrounds, Laclede Grounds, Gamble Lawn; DB and MR both mention first two, DB mentions Gamble Lawn)

1861: 3 (Lafayette Park, Gamble Lawn, Fairgrounds)

1862: 1 (Gamble Lawn)

1863: 3 (Gamble Lawn, Lafayette Park, Laclede Grounds)

1864/65: 2 (Gamble Lawn, Ham Street Grounds)

Known Grounds from 1859-1864/65 (5)

Fairgrounds

Gamble Lawn

Ham Street Grounds

Laclede Grounds

Lafayette Park

III. General Thoughts About The Data

Before I move on to talking about what the data means as far as St. Louis baseball during the Civil War is concerned, I just want to make some quick points about the data itself.

-I broke the data down into four categories: references to “base ball,” references to clubs, references to match games, and references to baseball grounds.

-References to “base ball,” generally, gives us an idea about the amount of baseball activity that was taking place. An increase in newspaper coverage, resulting in an increase in references to the game, usually indicates an increase in baseball activity and popularity. Looking at this gives us a good overview of what was happening. It's not perfect. It's not foolproof. But just looking at the number of general references to baseball in a newspaper at any given time gives us a quick idea of what was happening with the game.

-References to clubs and games gives us more specific data. Looking at only references to “baseball” doesn't give us any detailed indication of what was happening but only a general overview. You have to dig into those references to find the meat. The number of clubs playing and number of match games being played is a very good indication of the health of the game in a given area. An increase in clubs and games indicates growth in the popularity and health of the baseball. A decrease in clubs and games is good indication of a decrease in popularity and health.

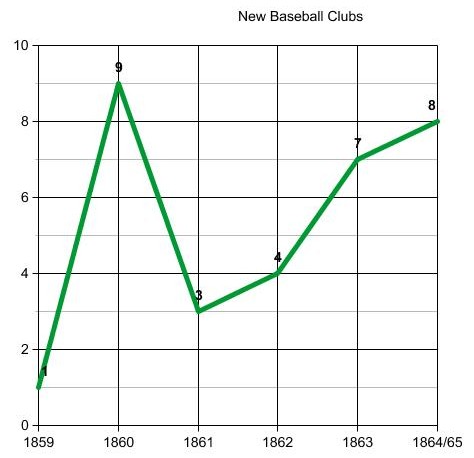

-A lot of the growth that we see in the number of clubs in St. Louis during the Civil War comes from an increase in the number of junior clubs. About a fifth of the known Civil War era St. Louis clubs were junior clubs that were, most likely, affiliated with a senior club. I count these as individual clubs but another way to look at this is that the senior clubs were growing and expanding. Also, I believe that the growth in junior clubs was a response to the substantial decrease in the number of playing-aged men in St. Louis. While it's still unknown exactly how many St. Louis men fought in the war, the number has to be around fifty or sixty thousand out of a total population of 160,000.

-I did not include all of the references to games played in this analysis because the data, with regards to the total number of games played, is incomplete. We don't know how many games were played during the war years in St. Louis because that information wasn't published in the newspapers. Most games were intramural games. They were played amongst the members of one club. The club would meet on what was called a club day, the members would divide up into two teams, and they would play baseball. That was the most common form of baseball being played at the time. A match game, involving a game played between two different clubs, was much more rare. It was an event and tended to receive more publicity in the newspapers. There were, however, other types of games that also received mention in the papers and these were the muffin games. These were gimmicky kind of games, played for fun. In St. Louis, there were numerous matches played between the married and single members of the club and the Empire Club's anniversary game often took this form. There were a few games where the members of several clubs got together and put together two teams to play a game – kind of like a modern all-star game. But I wanted to focus on match games because those are the kind of games we think of when we think of modern baseball. A baseball game is a game played between two competing clubs. But I just want to note here that there was plenty of other baseball being played in St. Louis besides these match games.

-I note the number of different places where baseball was played in St. Louis because I think an increase in the number of grounds being used is an indicator of a growing game. Also, I do it because I'm interested in the history of where, specifically, the game was played in St. Louis. There were, without a doubt, more grounds in use than was noted in the newspapers. The secondary sources probably give three or four more different grounds than I list here but I think the reason this list of Civil War-era baseball grounds is smaller than the list of known grounds (based on all sources) is that the papers were publishing information about the biggest games played in St. Louis during the war. They were, for the most part, telling us about the big match games and these games tended to be played at the better baseball grounds. They weren't going to play a big match game at Carr Square. Those grounds were fine for the Morning Star Club to use for club days but not if the Empires were playing the Unions and you were expecting a crowd. There were only so many places where you could play a game that had the room to host a crowd and was easy for that crowd to reach.

IV. Conclusions

The St. Louis data is unique. To show the uniqueness of the data, I want to compare it to information that we now have from the United States, generally, and Illinois and Chicago, specifically.

Recently Bruce Allardice presented his preliminary findings about the growth of the game in Illinois, which you can find at Protoball. Bruce did fantastic work in digging this information up and putting it all together. I think that his work is particularly useful as a baseline to which we can compare the St. Louis data. Bruce has absolutely inspired me and influenced the way in which I'm looking at and presenting this data.

[Note: The following charts come from Bruce's paper.]

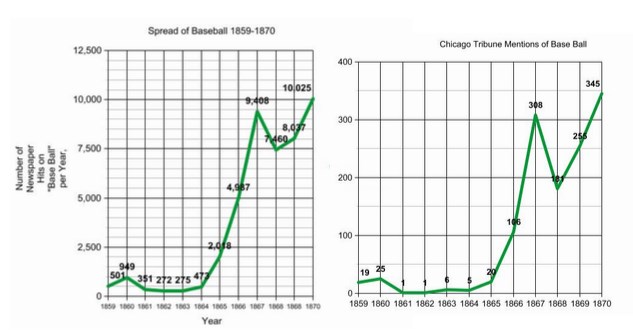

First, lets take a look at what Bruce found with regards to general references to “base ball” in the newspapers:

If we focus just on the Civil War years, we find that the references to “base ball” peaked in 1860, declined in 1861, remained flat through the war, and only began to recover in 1865. Most of the growth that we see in 1865, according to Bruce, actually occurred in the second half of the season, so that's not particularly relevant to our study. If we compare his findings to the St. Louis data, we find that the Missouri Republican had more references to “base ball” in 1861 than the Chicago Tribune had throughout the war. The Republican had more than three times the number of baseball references in 1863 than the Tribune did that year. Certainly, we can say that the Republican had better baseball coverage than the Tribune did during the war but, if we use general references to baseball as a proxy for general baseball activity then we can say that the St. Louis baseball scene was much more active than Chicago's. Also, we don't see the growth in 1861 and the later war years that we see in St. Louis in the nation as a whole.

Bruce, in his paper, also documented the number of new clubs formed:

Again, what we find in St. Louis during the war years is different that what Bruce found in Illinois and the United States. In St. Louis, we find steady growth in the number of new clubs, with more new clubs being formed every year from 1861 to 1865. The pattern actually holds through 1866, when there were around seventy new clubs formed in St. Louis. In Illinois, the number of new clubs formed during the war is negligible. In the country as a whole, we find a peak in 1860 and steady decline through 1863, when there were more clubs formed in St. Louis than in the rest of the nation combined. Bruce found fifty-one new baseball clubs formed during the Civil War. To the best of my knowledge, this does not include any of the St. Louis clubs, of which there were twenty-two. Adding the St. Louis clubs to Bruce's data increases the number of known new Civil War era clubs by forty-three percent.

There are two possibilities here. One, we don't have all of the national data. Bruce did a fantastic job digging up all of this information and he has expanded our knowledge of the early spread of baseball substantially. We can't give him an enough credit and praise for his efforts. But, the research never ends and there's always more to be found. I think that the patterns that Bruce presents are valid and a true representation of what was happening but we have to accept the possibility that there are more sources out there that need to be investigated.

The second possibility and the one that the data supports is that a substantial amount of the baseball activity taking place during the Civil War years was taking place in St. Louis. It's entirely possible that there was more baseball being played in St. Louis during the war years than anywhere else in the United States, except for New York. That is an extraordinarily significant finding. Prior to the analysis of this data, I don't think anyone would have suggest that this was the case. I think that everyone understands that St. Louis has a rich baseball history and tradition but I don't think that anyone would have suggested that St. Louis was one of the two biggest hotbeds of baseball during the Civil War.

I think that this information changes the way that we see the early history of the baseball, in general, and the history of the game in St. Louis, specifically. We always, and rightfully, think of New York and Brooklyn as the great hotbed of baseball during these years but we now have to account for the activity that was taking place in St. Louis during the Civil War. After a period of adjustment, in 1861 and 1862, it appears that baseball was thriving and growing in St. Louis in a way that it was not in the rest of the United States. This is in direct conflict with the major secondary sources, which have led us to believe that there was little baseball activity in St. Louis during the war years. Those sources, which are still invaluable, have been proven wrong by an investigation and analysis of the contemporary source material.

There is more work and more research that needs to be done on this subject. I know of at least one more St. Louis newspaper that I need to go through before I can say that I've exhausted the primary source material and I believe that digging through that will yield more and interesting information about baseball in St. Louis during the Civil War. But as things currently stand, with the information that we have, it's possible to present a unique and interesting picture of Civil War era baseball in St. Louis and to reach some fascinating conclusions. We now know that the war did not suppress baseball activity in St. Louis. We now know that the game was growing in the city during those years, especially in the last two years of the war. And we also now know that St. Louis was one of the great hotbeds of the game during the Civil War.

We now know substantially more than we did before about baseball in St. Louis during the Civil War and, as a researcher and historian, that pleases me. I firmly believe that with time and effort we will discover and learn more. The nature of baseball during the war – its evolution, spread, and growth – is something that we're learning more about everyday. There's so much work going on in this area and it's bearing fascinating fruit. We no longer have to depend on myth and legend. We can find the primary source material and look at it ourselves, reaching our own conclusions and discovering the truth of the matter. The dark age – the saeculum obscurum - is ending and we have the ability to shine a light onto the past and discover it once again.